Table of Contents

Value-Based Care (VBC) is a healthcare delivery model that emphasizes value over volume – meaning providers are rewarded for better patient outcomes and efficiency rather than the number of services performed. This model has emerged in response to rising costs and uneven quality in the traditional fee-for-service system. In recent years, the U.S. healthcare system has been undergoing a significant evolution from volume to value, driven by the need to improve quality of care, enhance patient experiences, and control costs. Below, we provide a comprehensive glossary-style guide to value-based care, including its definition, key principles, examples, benefits, challenges, and more.

From Volume to Value: The Evolution of Healthcare Delivery

For decades, healthcare providers were mostly paid under a fee-for-service (FFS) model that financially rewarded quantity of care – every test, procedure, or visit generated a payment. This volume-driven approach often led to fragmented care, unnecessary procedures, and skyrocketing costs, without commensurate improvement in health outcomes. In fact, the United States spends nearly one-fifth of its GDP on healthcare (far more than any other nation), yet health outcomes in the U.S. often lag behind those of other high-income countries.

America has historically seen higher rates of preventable illness and lower life expectancy relative to its spending, indicating that pouring more money into healthcare doesn’t automatically yield better results. A major reason is the misaligned incentives of FFS: providers are paid for each service delivered, so income rises with volume – even if those services don’t improve a patient’s health.

This imbalance created an urgent need for change. Policymakers, insurers, and health systems began seeking models that would realign incentives toward quality, outcomes, and cost-efficiency in healthcare. Enter value-based care – an approach that ties payment to the value delivered. Instead of rewarding volume, VBC programs reward providers for keeping patients healthy, managing chronic conditions proactively, and avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations. The concept gained momentum in the 2000s and 2010s through initiatives like Medicare pilot programs, the Affordable Care Act’s payment reforms, and private sector innovation.

By focusing on value, healthcare organizations aim to achieve the “Triple Aim”: better patient experience, improved population health, and reduced per-capita costs. The evolution is ongoing, with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) setting ambitious goals (for example, CMS aims to have all Medicare beneficiaries in accountable, value-based arrangements by 2030) – a strong indication that value-based care is the future of U.S. healthcare.

What is Value-Based Care? (Definition and Overview)

Value-Based Care is a healthcare reimbursement model that ties the payments for care delivery to the quality of care provided and the outcomes achieved. In simple terms, providers are paid based on patient health outcomes, not just services rendered. If care is delivered effectively – patients get healthier, experience fewer complications, and healthcare spending is used wisely – the provider earns more. If outcomes falter or costs run wastefully high, payments to providers may decrease. This contrasts sharply with the old model where a hospital or doctor could bill for each test or treatment regardless of necessity or result.

Under value-based care programs, healthcare outcomes (such as recovery rates, disease control, patient satisfaction) and cost-efficiency become key metrics. Providers are held accountable for improving patient outcomes and reducing avoidable costs. Quality of care, patient experience, and even equity is emphasized, with incentives for meeting targets in these areas. For example, a clinic might receive a bonus for achieving high rates of controlled blood pressure in its hypertensive patients (a positive outcome), while also keeping total treatment costs under a certain benchmark.

Crucially, value-based care isn’t a one-size-fits-all program but a broad philosophy applied through various specific models (which we’ll cover later). Whether through bonuses for high performance or penalties for poor performance, the central idea is the same: better care = better rewards. This encourages healthcare providers to invest in preventive care, care coordination, and patient engagement – strategies that help avoid expensive interventions by keeping patients healthier in the first place. By aligning payment with health outcomes and patient-centered care, VBC aims to transform the healthcare system into one that delivers higher quality at lower cost.

Key Pillars of Value-Based Care

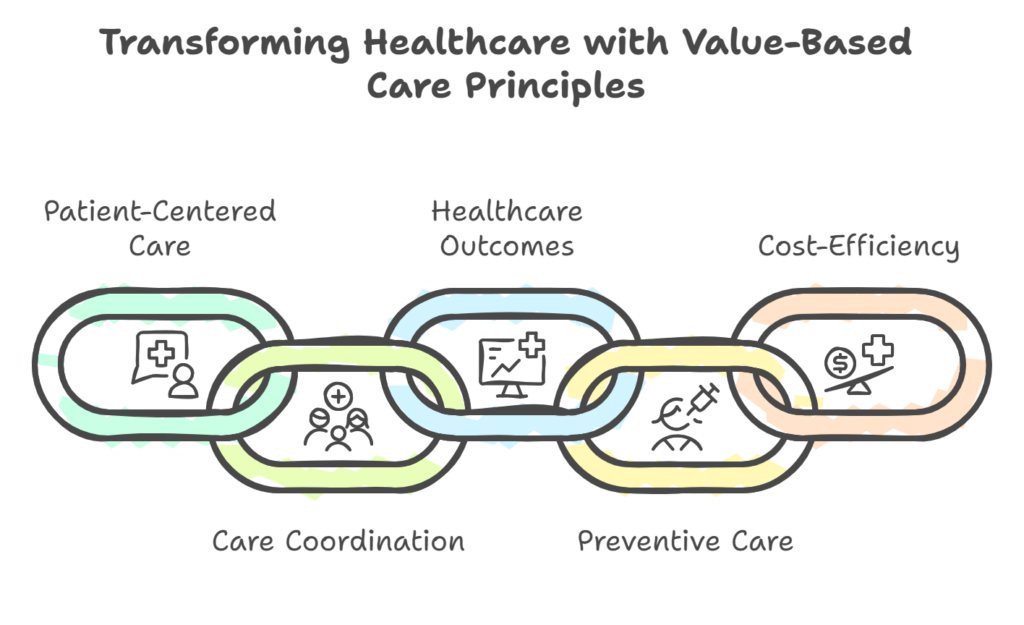

Value-based care rests on several core principles that distinguish it from the fee-for-service approach. Here are the key pillars of value-based care:

1. Patient-Centered Care and Personalization

At the heart of value-based care is an unwavering focus on patient-centered care. This means healthcare providers tailor treatment plans to each patient’s unique needs, preferences, and values. Instead of a one-size-fits-all mentality, clinicians emphasize personalized care and take time to engage with patients. For example, under a patient-centered approach, a primary care doctor might spend extra time educating a patient about managing diabetes or involve the patient in shared decision-making about treatment options. The goal is to improve patient satisfaction and ensure care is delivered with the patient, not just to the patient. By prioritizing patient experience and engagement, value-based models foster trust and better communication, which in turn can lead to higher adherence to care plans and improved health outcomes.

2. Care Coordination and Integrated Team-Based Care

Effective care coordination is essential for meeting value-based care goals. In the traditional system, care is often fragmented – specialists, primary care doctors, hospitals, and post-acute care providers might all operate in silos. Value-based care breaks down these silos by encouraging team-based care across the continuum. Providers (physicians, nurses, specialists, pharmacists, social workers, etc.) work in unison to manage a patient’s care journey, especially for chronic conditions or complex cases. Care coordination ensures that important information is shared among providers, that there are no gaps or unnecessary duplications in treatment, and that patients receive seamless care.

For instance, a value-driven care team might implement regular care management meetings to review high-risk patients, ensuring everyone from the cardiologist to the nutritionist is on the same page. This collaborative approach improves safety and outcomes – patients are less likely to “fall through the cracks.” It also aligns with patient-centered care, since the care team collectively supports the patient’s overall well-being, including aspects like mental health or social needs that traditional models might overlook.

3. Focus on Healthcare Outcomes and Quality of Care

Value-based care is fundamentally outcomes-driven. Success is measured not by how many services were provided, but by how well patient’s fare. Key healthcare outcomes include metrics like hospital readmission rates, infection rates, management of chronic disease indicators (e.g. blood sugar levels for diabetics), mortality rates for certain conditions, and patient-reported outcomes (like functional improvement or quality of life). A focus on healthcare outcomes means that providers must rigorously measure and track the quality of care they deliver.

Programs often tie payment bonuses or penalties to specific quality metrics – for example, achieving a high percentage of patients with controlled hypertension, or screening a large portion of eligible patients for cancer. By keeping a spotlight on outcomes and quality, VBC initiatives drive providers to continuously improve. They might adopt evidence-based best practices, invest in better training, or use data analytics to identify where care falls short. In short, improving healthcare outcomes is the north star of value-based care. When outcomes improve – fewer complications, faster recoveries, healthier patients – it’s a win for patients, providers, and payers alike.

4. Preventive Care and Chronic Disease Management

Another pillar of value-based care is a proactive approach to health through preventive care and robust chronic disease management. Instead of waiting for patients to get sick and then reacting (as often happens in fee-for-service medicine), value-based models invest in keeping patients healthy. This includes routine preventive services like vaccinations, screenings (mammograms, colonoscopies, etc.), and wellness visits, as well as patient education on lifestyle factors. It also involves actively managing chronic illnesses – for example, ensuring a patient with asthma has proper medications and a self-management plan to prevent ER visits, or that a patient with heart failure gets timely follow-ups to avoid hospitalization.

By addressing issues upstream, providers can prevent costly complications down the line. The value-based framework supports this by reimbursing things that traditionally were harder to bill for under FFS, such as counseling, care management, or nutrition guidance. In practice, a clinic might deploy care managers or health coaches to regularly check in on patients with diabetes between doctor visits, helping them with diet, medication adherence, and symptom monitoring. These preventive efforts improve patient health outcomes and reduce emergency visits or hospitalizations, contributing to the overall cost-efficiency of care.

5. Accountability for Cost-Efficiency in Healthcare Delivery

“Value” in healthcare is often defined as the health outcomes achieved per dollar spent. Thus, cost-efficiency in healthcare is a critical pillar of value-based care. Providers are expected to eliminate wasteful spending and use resources wisely while maintaining or improving quality. This might mean choosing a less invasive treatment that achieves the same result as an expensive surgery or reducing duplication of tests by sharing records among providers. In value-based contracts, doctors and hospitals become accountable for the total cost of care for their patient population. They are encouraged to avoid unnecessary tests, procedures, or hospital days that don’t add value.

For example, if a certain imaging test won’t change the management of a patient’s condition, a value-focused provider might forgo it, whereas in a volume-based system there was a financial incentive to do it anyway. Cost-efficiency also comes from preventing costly health crises (as noted in the preventive care pillar) and managing care transitions smoothly (to avoid readmissions). Many value-based programs track spending against targets: if providers reduce costs while hitting quality goals, they share in the savings; if they overspend or quality suffers, they may incur penalties. By linking financial outcomes to efficient care delivery, value-based care motivates providers to continually seek ways to deliver high-quality care at a lower cost – the essence of better value.

Value-Based Care Reimbursement Models (How Providers Get Paid)

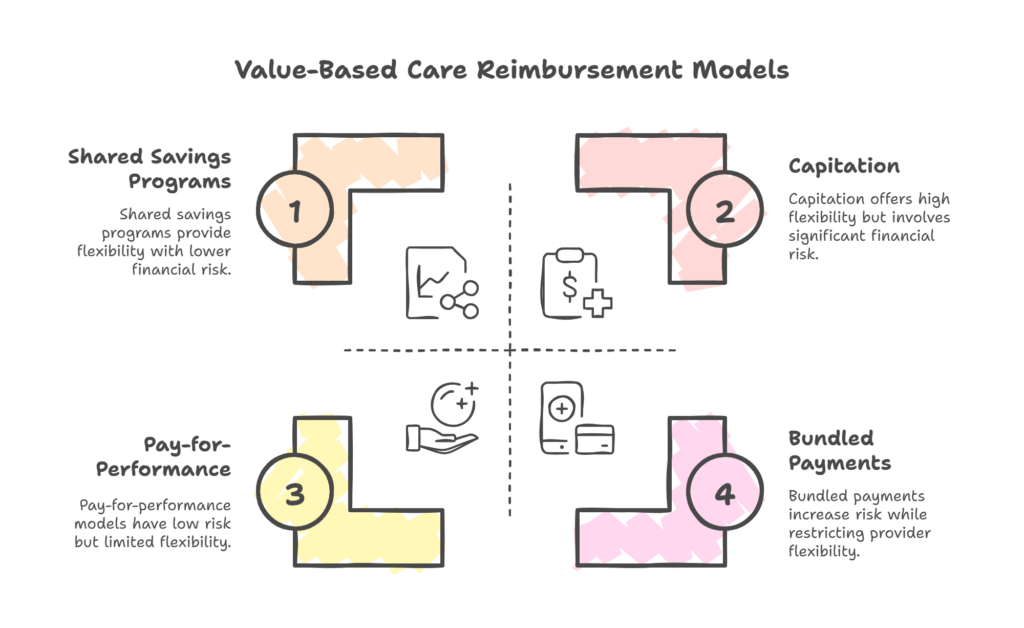

There are several reimbursement models under the umbrella of value-based care. These models are often referred to as alternative payment models (APMs) because they differ from standard fee-for-service. Each model aligns financial incentives with quality and outcomes in a slightly different way. Major value-based reimbursement models include:

1. Pay-for-Performance (P4P):

In this model, providers continue to receive fee-for-service payments, but with an overlay of bonuses or penalties based on performance metrics. If a provider meets or exceeds predefined quality and outcome benchmarks, they earn incentive payments; if they underperform, their payments may be adjusted downward. For example, under Medicare’s Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), clinicians are scored on measures of quality (outcomes), cost efficiency, use of technology, etc., and their future Medicare reimbursements go up or down accordingly. Pay-for-performance rewards quality over quantity, nudging providers to focus on things like preventive care, patient satisfaction, and effective management of chronic conditions.

Some P4P programs also include downside risk, meaning providers can lose money for poor results, making them even more accountable. Another variant of this category is Bundled Payments (Episode-of-Care Payments) – where a single bundled payment is provided for all services related to a specific treatment or procedure (e.g., a knee replacement surgery and all rehab). Providers must then coordinate the entire episode efficiently; if they manage the episode under the budget and meet quality standards, they keep the savings (or get a bonus). If not, they may not be fully reimbursed for overruns. This approach incentivizes teamwork and avoiding complications.

2. Shared Savings Programs (Accountable Care Organizations):

Shared savings models encourage providers to work together to manage the total cost of care for a population of patients. A prime example is the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) for Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). In an ACO, a group of providers (e.g., a hospital plus affiliated doctors and clinics) is collectively responsible for the health outcomes and spending of a defined patient population (such as 20,000 Medicare beneficiaries). The payer (Medicare or an insurer) sets a spending benchmark based on historical costs. If the ACO’s patients are cared for at lower total cost than the benchmark – and certain quality targets are met – the ACO shares in the savings achieved. For instance, an ACO that saves Medicare $10 million might receive half of that as a reward, distributed among the participating provider organizations.

This shared savings approach motivates providers to eliminate waste and invest in care improvements that reduce expensive utilization (like avoidable hospital admissions). Some programs also have shared risk, meaning if the providers overspend (costs exceed the benchmark) or miss quality goals, they may have to pay back a portion of the losses. This two-sided risk model heightens accountability by putting providers’ own revenue on the line, although uptake is slower due to the financial risk involved.

3. Capitation (Population-Based Payments):

Capitation is the most advanced form of value-based reimbursement, involving prospective, upfront payments to care for patients. Under capitation, a provider (or health system) is paid a fixed amount per patient per month (often called PMPM payment), covering all the healthcare needs of that patient. This model is essentially a flat subscription fee for healthcare services. For example, a physician group might receive $500 per member per month for each enrolled patient, and out of that must pay for any and all care the patient requires – primary care visits, specialist consults, hospitalizations, medications, etc.

If the providers can keep patients healthy and costs low, they keep any surplus as profit; if patients require lots of expensive care, the providers incur those costs, potentially reducing their margin. Global capitation (covering all services) puts providers in the position of being fully accountable for cost and quality – it strongly incentivizes preventive care, proactive chronic disease management, and avoidance of unnecessary procedures.

An example is Medicare Advantage plans, where private insurers receive capitated payments from Medicare and often pay provider groups via capitation to manage seniors’ care. Another example is PACE (Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly), where organizations receive a fixed per-person payment to provide comprehensive care for frail elders. Capitation provides predictable revenue for providers and maximum flexibility in how they deliver care, but it requires sophisticated care management and data analytics to be successful. Notably, even with capitation, quality measures still apply – providers must meet outcome and patient satisfaction benchmarks, or they could face other penalties or contract loss.

These models aren’t mutually exclusive – a single healthcare organization might participate in multiple value-based programs simultaneously. For instance, a hospital could be part of an ACO (shared savings) while also adhering to a pay-for-performance hospital readmission reduction program. What they all share is the shift in financial incentive: from paying for services to paying for value. By using these reimbursement models, payers (like Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers) aim to spur innovation in how care is delivered, pushing providers to find new ways to improve quality and cost-efficiency in healthcare.

Benefits of Value-Based Care

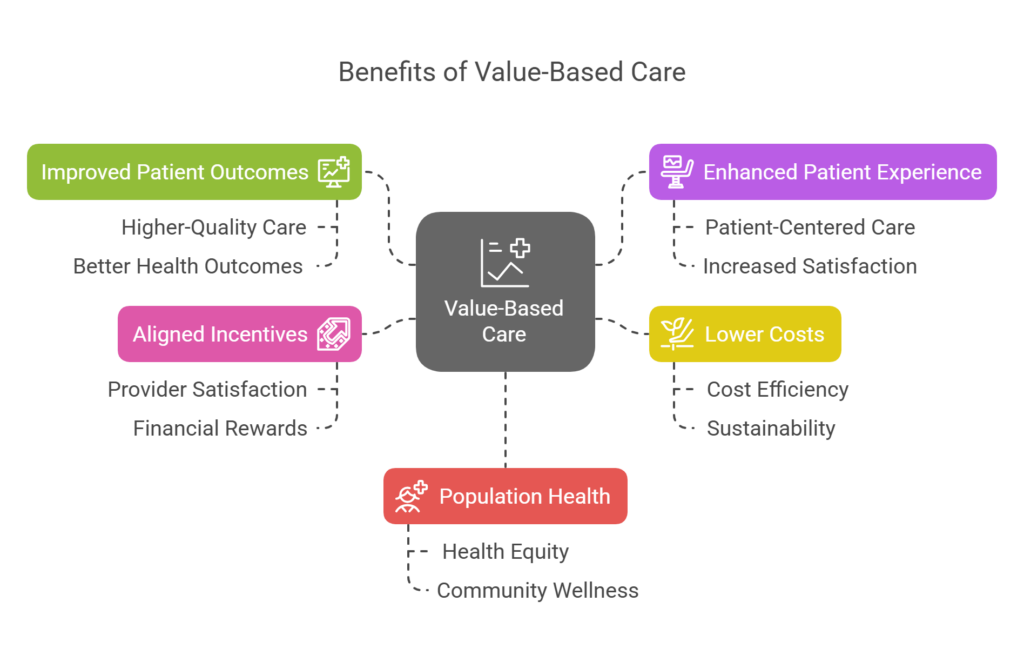

When implemented well, value-based care can deliver significant benefits to all stakeholders in the healthcare system – patients, providers, payers, and the healthcare system as a whole. Here are some of the key benefits of moving to a value-based model:

1. Improved Patient Outcomes and Quality of Care:

The most important benefit is that patients receive higher-quality care and enjoy better health outcomes. With providers focused on keeping people healthy (not just treating them when sick), patients experience fewer complications, better management of chronic diseases, and improved overall wellness. For example, value-based initiatives have been associated with lower hospital readmission rates and higher rates of preventive screenings. Patients with complex conditions get more personalized, coordinated care, leading to safer and more effective treatments. In short, value-based care means patients get the right care at the right time, which translates to healthier, longer lives.

2. Enhanced Patient Experience and Satisfaction:

Because of its patient-centered care approach, value-based care often leads to higher patient satisfaction. Patients typically report better experiences when their providers spend time listening, involve them in decision-making, and coordinate their care seamlessly. In a value-based setting, providers are incentivized to keep patients happy and healthy – for instance, they may provide access to care coaches or offer extended office hours to prevent urgent care visits. This emphasis on the patient’s needs results in more engaged patients who take active roles in their health. A stronger patient-provider relationship built on trust and communication is a hallmark of value-based models, and it contributes to patients feeling more cared for and respected.

3. Lower Costs and Cost-Efficiency:

A major promise of value-based care is cost efficiency in healthcare – delivering better care at a lower cost. By reducing unnecessary tests and procedures, avoiding hospitalizations through preventive care, and eliminating waste, value-based programs can significantly decrease healthcare costs for payers and patients alike. For instance, the case studies above showed millions in savings and slower cost growth. Patients can also see lower out-of-pocket expenses when costly interventions are averted (for example, controlling a condition with medication and lifestyle changes is cheaper than emergency surgery that might be needed if the condition were unmanaged). Additionally, when the health system saves money, those savings can be passed along in the form of lower insurance premiums or reinvested into community health. In essence, value-based care addresses the long-term cost sustainability of healthcare – a critical benefit as the nation grapples with healthcare affordability.

4. Aligned Incentives and Provider Satisfaction:

In a value-based care environment, providers’ incentives are aligned with patient well-being. Doctors, nurses, and hospitals succeed financially when they help their patients get healthier – a goal that aligns with the fundamental mission of healthcare. This alignment can be professionally rewarding for providers. Many clinicians prefer focusing on quality over quantity; they often report greater job satisfaction when they can practice medicine in a way that emphasizes outcomes and patient relationships rather than rushing through high volumes of visits.

Early adopters of value-based models (like those in patient-centered medical homes or ACOs) have noted improvements in workflow and teamwork, and some have seen reductions in burnout as care becomes more team-oriented and less administratively heavy on a per-service basis. Additionally, providers who excel under value-based contracts can benefit from financial bonuses and shared savings, potentially earning more reimbursement than under fee-for-service. This can make practices more financially stable in the long run, especially as value-based payments from Medicare and other payers continue to grow.

5. Population Health and Health Equity:

Value-based care encourages looking at the health of populations and addressing systemic issues. Providers are incentivized to track outcomes across different groups and identify care gaps. This leads to initiatives targeting social determinants of health and disparities. For example, a value-based program might reward closing the gap in blood pressure control between different racial groups, prompting providers to develop outreach programs in underserved communities. By focusing on population health management, value-based care can drive improvements in preventive care uptake, chronic disease control, and overall community wellness.

Over time, this contributes to a healthier population with fewer health disparities. Furthermore, some newer value-based care models explicitly include health equity as a performance metric (for instance, the ACO REACH model by Medicare places emphasis on reducing disparities). This means providers are starting to be rewarded for improving care for historically underserved groups, which is a positive step toward a more equitable healthcare system.

In summary, value-based care offers a more sustainable, patient-friendly, and outcome-oriented approach to healthcare. When patients are healthier and happier, providers are rewarded for good care, payers spend less on avoidable complications, and the healthcare system operates more efficiently, everyone wins. These benefits explain why both public and private sectors are actively pushing the shift from volume to value.

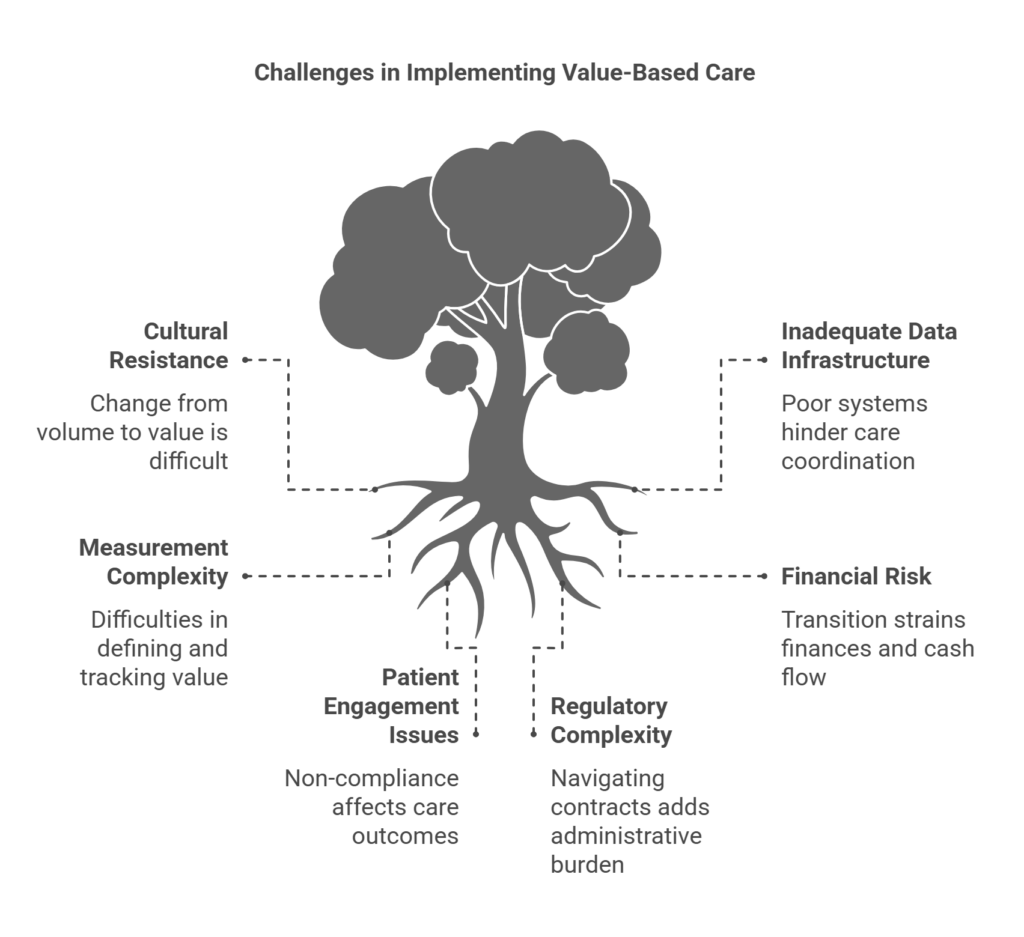

Challenges of Implementing Value-Based Care

While the benefits of value-based care are compelling, transitioning to this model is not without challenges. Healthcare organizations often face obstacles when implementing value-based programs. Some of the notable challenges of value-based care include:

1. Cultural Shift and Buy-In:

Switching from a volume-driven mindset to a value-driven one requires a significant culture change within healthcare organizations. Physicians and staff accustomed to the fee-for-service ethos (maximize throughput, see more patients, etc.) must adjust to new priorities like care coordination, documentation of outcomes, and teamwork. This can encounter resistance. Gaining buy-in from providers is crucial – they need to trust the value-based model and believe that focusing on quality will ultimately be rewarded. Change management and education are needed to help clinicians understand the new incentives and adapt their practices. Overcoming the inertia of “how we’ve always done it” is often the first hurdle in implementing VBC.

2. Data and Technology Infrastructure:

Data-driven care is essential for value-based programs – providers must track outcomes, costs, and utilize information to guide care. Many organizations struggle with inadequate health IT infrastructure and poor interoperability (the ability for different systems and providers to share patient information). Implementing value-based care often means investing in better electronic health records systems, data analytics tools, and care management platforms. These systems must aggregate data across settings to give a full picture of a patient’s journey.

If a provider cannot easily access a patient’s specialist reports or hospital records, it’s difficult to coordinate care or measure outcomes. Interoperability remains a challenge; many providers still operate on disparate systems that don’t communicate well. Additionally, advanced analytics are needed to identify high-risk patients, track performance on quality metrics in real-time, and pinpoint areas for improvement. Building or purchasing this infrastructure can be costly and technically challenging, especially for smaller practices or those in rural areas.

3. Measuring Value and Outcomes:

Defining and measuring “value” in healthcare is complex. There are hundreds of potential quality measures and differing opinions on which outcomes truly reflect good care. Providers may feel burdened by reporting requirements and skeptical about whether the metrics used truly capture their performance. For example, should success be measured by patient blood pressure levels, patient satisfaction scores, hospital readmission rates, or all of the above? Often, it’s “all of the above,” which can create a heavy administrative load to collect and report data.

Measurement complexity can also lead to gaming the system (focusing only on measured aspects at the expense of unmeasured ones) or frustration if providers feel the targets are unattainable or not entirely within their control. There is ongoing debate and refinement in the industry about how to best measure outcomes and value fairly. Until measurement is more streamlined and aligned across payers, it remains a challenge.

4. Financial Risk and Transition Strain:

Value-based care often requires providers to take on financial risk for patient outcomes. This can be daunting, especially for organizations with tight margins. In models with downside risk (like two-sided ACOs or capitation), a bad year of outcomes or a few very expensive patients could mean the provider loses money. Smaller practices might not have the financial reserves to weather such variability, making them hesitant to join advanced value-based programs. Even in upside-only models, the transition can strain finances: as care improves and unnecessary utilization drops, providers might see reduced fee-for-service revenue before shared savings or bonuses make up the difference.

Essentially, there can be a short-term cash flow dip during the transformation. Balancing the old payment system and the new one is tricky – many providers are in a hybrid environment where they still rely on fee-for-service for a portion of their income while trying to increase their value-based revenue. This duality requires careful financial planning. Additionally, investments in care coordinators, new software, or patient programs create upfront costs in hopes of downstream savings. All these factors make the financial aspect of VBC adoption a challenge, particularly for those without substantial capital or support.

5. Patient Engagement and Compliance:

Achieving success in value-based care isn’t only on providers – it also relies on patients becoming active participants in their health. Encouraging patients to stick to treatment plans, make healthy lifestyle changes, and engage in preventive care is not always easy. If patients do not show up for routine check-ups, don’t take their medications, or ignore outreach by care managers, the best-laid plans of a value-based program can falter. Ensuring patient engagement is a constant challenge.

Providers may need to develop creative solutions to motivate and educate patients – from health coaching and patient portals to community health workers who can bridge cultural or socioeconomic gaps. Despite these efforts, some patients remain difficult to reach or involve, which can impact outcome metrics negatively. This means providers carry a certain risk related to patient behavior that is outside their direct control, making it a challenging aspect of delivering value-based care consistently.

6. Regulatory and Contractual Complexity:

Navigating the myriad value-based care programs and payer contracts can be complicated. Each payer (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurers) may have different rules, metrics, and structures for their value-based models. Keeping track of these and ensuring compliance with regulations (for example, Stark Law and Anti-Kickback statute waivers for care coordination, HIPAA considerations in data sharing, etc.) adds administrative burden. Smaller organizations often find it challenging to negotiate favorable value-based contracts or understand the fine print that determines their financial outcomes.

Moreover, the policy environment is evolving – new models (like Medicare’s Direct Contracting/ACO REACH) come and older one’s sunset, requiring organizations to continuously adapt. Regulatory changes or uncertainty (such as changes in government leadership or policy priorities) can also make long-term planning for VBC difficult. In short, the complexity of healthcare regulation and payer contracts is a non-trivial hurdle in moving to value-based care.

Despite these challenges, the momentum behind value-based care continues to grow. Many healthcare organizations have found ways to overcome these obstacles by starting with pilot programs, investing in training, partnering with technology firms, or joining larger networks like ACOs that provide support. It’s widely recognized that while implementing value-based care is challenging, the status quo is unsustainable – thus, stakeholders are working through these issues, and each year best practices become clearer as more data and experience accumulates.

Conclusion: Embracing Value-Based Care for a Sustainable Healthcare Future

Value-based care represents a fundamental shift in how healthcare is delivered and reimbursed. By aligning financial incentives with patient health outcomes, it encourages everyone in the system to prioritize what truly matters: keeping patients healthy, providing high-quality, patient-centered care, and using resources wisely. The transition from fee-for-service to value-based models is already underway, and it’s increasingly clear that this is not just a passing trend but a permanent transformation in healthcare. As demonstrated by early adopters, value-based care can lead to healthier patients, smarter spending, and happier providers – the goals that healthcare reform has long sought to achieve.

For healthcare professionals, administrators, and managed service organizations, the key takeaway is that now is the time to embrace value-based care. Doing so may involve investing in new care management programs, upgrading data systems, training staff in team-based care approaches, or collaborating more closely with payers and other providers. The effort is worthwhile: organizations that successfully implement value-based strategies often become leaders in their communities, delivering superior outcomes and enjoying financial rewards from shared savings or performance bonuses. In an environment where CMS and major insurers are steadily expanding value-based payment programs, getting ahead of the curve is wise.

Call to Action: Healthcare leaders and providers should start by assessing their current performance on quality and outcomes and identify areas where value-based initiatives could make an immediate impact (such as launching a care coordination program for high-risk patients or joining an Accountable Care Organization). Engage your teams in the mission of value-based care – emphasize how focusing on patients’ long-term wellness is rewarding both medically and financially. Seek out partnerships or expert resources if needed, because success in value-based care often requires collaboration and shared learning.

By taking proactive steps now, you can position your organization to thrive in the emerging value-driven healthcare landscape. The sooner you align your care delivery with the principles of value-based care, the better prepared you will be to deliver exceptional outcomes for your patients and sustainable growth for your practice or health system. Embracing value-based care today is an investment in a healthier, more efficient tomorrow.

Frequently Asked Questions about Value-Based Care

What is the difference between value-based care and fee-for-service care?

Value-based care (VBC) and fee-for-service (FFS) are two fundamentally different healthcare payment models. Under fee-for-service, providers are paid for each service they perform – every office visit, test, procedure, or hospital stay generates a separate fee. This means income is tied to volume, rewarding quantity over quality. A major drawback of FFS is that it can lead to overutilization of services and doesn’t necessarily encourage coordination or preventive care (since providers are paid even if the services were duplicative or avoidable). In contrast, value-based care ties provider payments to patient outcomes and overall value delivered. In VBC models, providers might receive a lump sum to manage a patient’s care or bonuses for meeting quality targets, rather than a piecemeal fee for each intervention.

The key difference is what is being rewarded – FFS rewards doing more, while VBC rewards doing better (achieving healthier patients at lower cost). For example, under FFS a doctor might be paid separately for each diabetes check-up and complication treated, whereas under VBC the doctor could receive a monthly payment to manage the diabetic patient’s health and would earn more if that patient stays stable and complication-free. In summary, fee-for-service = pay for volume, whereas value-based care = pay for value (quality and outcomes). VBC encourages care that is patient-centered, preventive, and efficient, whereas FFS can inadvertently encourage high volumes of tests or treatments even when not necessary.

What are the benefits of value-based care?

Value-based care offers numerous benefits, which is why it’s being widely promoted in the healthcare industry. Key benefits include:

- Better Patient Outcomes: Patients typically enjoy healthier results under VBC because providers focus on preventive care and chronic disease management. This means fewer hospitalizations, better controlled chronic conditions, and higher survival and recovery rates for illnesses.

- Higher Quality of Care: Providers are incentivized to follow best practices and maintain high standards of care. Patients often receive more comprehensive, coordinated services, leading to a higher quality healthcare experience (with less fragmentation than in traditional systems).

- Lower Healthcare Costs: By avoiding unnecessary procedures and preventing health crises before they happen, value-based care can significantly reduce costs. There’s less wasteful spending on redundant tests or hospital readmissions, which saves money for patients, insurers, and the system overall.

- Improved Patient Experience: Value-based models are patient-centered, which usually translates to more time with healthcare providers, shared decision-making, and care that respects patients’ needs and preferences. This often leads to greater patient satisfaction and trust in the healthcare system.

- Incentives for Providers: Clinicians and hospitals benefit by being rewarded for effective care. They may receive bonus payments or a share of savings when they deliver good outcomes. This alignment of incentives can also improve provider morale and reduce burnout, as doctors see tangible results (both in patient health and financial rewards) from quality improvement efforts.

Overall, value-based care creates a win-win: patients get healthier and more satisfied with their care, while the healthcare system operates more efficiently and cost-effectively.

How do providers get paid in value-based care?

In value-based care, provider payment is structured around alternative reimbursement models that reward quality and efficiency. Unlike the straightforward fee-for-service billing per procedure, VBC payments come in a few common forms:

- Performance Bonuses or Penalties: Providers might still bill normally for services, but afterward their payments are adjusted based on performance. For example, a clinic could earn a bonus for a high patient flu vaccination rate or face a penalty if their hospital readmission rate is above a certain benchmark. This is often called pay-for-performance, where meeting quality metrics leads to higher pay.

- Shared Savings Arrangements: Providers (often as part of an ACO or network) are given a target budget for the year. If they manage to keep patients’ total care costs below that target while hitting quality goals, they share in the savings. For instance, if an ACO saves an insurer $5 million, the provider group might receive 50% of that savings as a reward. This encourages cost control and care coordination. In some contracts, if costs run over the target, providers might also share in the losses (this is known as two-sided risk).

- Bundled Payments: Under a bundled payment, a single combined payment is made for all services related to a specific treatment or episode of care. For example, rather than paying a surgeon, anesthesiologist, hospital, and rehab facility separately for a knee replacement, the payer provides one bundled payment that covers the entire episode. The healthcare providers then divide that payment. If they can deliver the whole episode of care for less than the bundle amount (while meeting quality standards), they can keep the leftover as profit – but if they overspend or quality suffers, they may not be reimbursed for the excess cost.

- Capitation Payments: Some value-based programs use capitation, where providers are paid a fixed amount per patient (per month or per year) to cover all needed care. For example, a primary care group might get $30 per patient per month to manage each patient’s care. This prepaid approach gives providers upfront revenue and full accountability – they must budget that money to cover all of a patient’s care (sometimes specific services like specialty care or drugs might be carved out, depending on the contract).

If they keep patients healthy and use fewer resources, they essentially keep the savings; if patients need a lot of services, the provider must absorb the extra cost. Capitation strongly incentivizes preventive, efficient care, since the payment is the same no matter how much service is delivered – so avoiding an expensive hospitalization benefits the provider financially.

In practice, many providers in value-based care participate in a mix of these models. For instance, a large health system might have some fully capitated contracts (e.g., managing an HMO population), some ACO shared savings contracts for Medicare patients, and various pay-for-performance bonuses with different insurers. The unifying theme is that money is tied to outcomes and cost performance. Providers earn more by keeping their populations healthy and meeting metrics, rather than by simply increasing service volume. This payment structure is designed to support the work that goes into proactive patient management – things like care coordination, patient education, and follow-up outreach – which aren’t explicitly paid for in a pure fee-for-service world.

What are the challenges of implementing value-based care?

Implementing value-based care can be challenging for healthcare organizations. Some common challenges include:

- Transitioning Financially: Moving from fee-for-service to value-based payments can strain finances. Providers often have to invest in new systems (like data analytics or care management staff) upfront, and there may be a lag before they see returns from shared savings or bonuses. Managing cash flow during this transition and taking on financial risk for patient outcomes can be tough, especially for smaller practices.

- Data Collection and Analytics: Value-based care requires robust data on quality metrics, costs, and patient outcomes. Collecting, integrating, and analyzing this data is a major hurdle. Many providers face challenges with EHR interoperability (different systems not talking to each other) and the need for advanced analytics to track performance in real time. Without good data, it’s hard to succeed in VBC, but setting up that data infrastructure is neither cheap nor easy.

- Changing Provider Mindset and Workflows: Adopting value-based care often means redesigning care processes – for example, implementing team huddles for care coordination, following up with patients by phone, or adding social workers to the team. It’s a different way of working. Not all clinicians are immediately on board with these changes; some may be accustomed to the autonomy and pace of fee-for-service practice. Cultural resistance and the learning curve for new workflows can slow down implementation. It takes strong leadership and training to get everyone aligned with the value-based approach.

- Ensuring Patient Engagement: Value-based care’s success partly hinges on patients taking an active role in their health (e.g., attending wellness visits, managing chronic conditions, following care plans). Engaging patients can be challenging – socioeconomic factors, health literacy, and trust in the healthcare system all play a role in whether patients participate fully. Providers have to find ways to motivate and support patients, which might include extra outreach, education, or addressing barriers like transportation and cost of medications. Without engaged patients, hitting outcome targets (like lower A1c levels in diabetics, or better medication adherence) is more difficult.

- Navigating Multiple Programs: There isn’t a single value-based care program but many, each with its own rules and metrics (Medicare has several, every insurer might do it a bit differently). For providers contracting with multiple payers, the administrative complexity can be overwhelming. They might have to report dozens of different quality measures to different entities and keep track of various incentive structures. This complexity can cause “program fatigue” and make it hard to focus efforts. Standardizing and simplifying value-based programs is an ongoing need, but until that happens, providers must carefully manage the myriad requirements, which is a challenge in itself.

Despite these challenges, most healthcare organizations acknowledge that value-based care is the direction of the future. Many are starting incrementally – perhaps joining one or two programs to learn the ropes – and are investing in the necessary tools and partnerships to overcome these hurdles. Over time, as both technology and care models mature, implementing value-based care is expected to become easier and even the new norm. For now, though, it requires effort, investment, and adaptability to make the shift successfully.